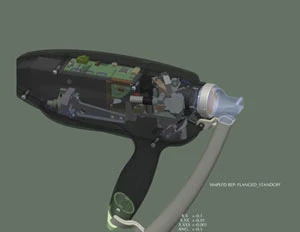

Laser skin resurfacing is one of the fastest growing application areas for medical lasers. When aesthetic laser manufacturer Cutera Inc. began to develop an innovative skin-resurfacing laser called the Pearl, their engineers turned to motors from MicroMo Electronics Inc. to provide precision motion in a compact, lightweight assembly. Although the pioneering work in skin resurfacing was done with carbon dioxide lasers operating at 10.6µm and erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (Er:YAG) emitting at 2.94µm, Cutera wanted to leverage a more exotic laser material called erbium-doped yttrium scandium gallium garnet (Er:YSGG; 2.79µm). The shorter wavelength offers a different tissue interaction from that of other aesthetic lasers, and that wavelength difference also requires tradeoffs. In most skin-resurfacing systems, the laser itself resides in the base of the instrument and an articulated arm transmits the light to the handpiece. One option was transmission by optical fiber, but the wavelength emitted by Er:YSGG cannot propagate through standard fiber, and IR-transmitting fibers are expensive, fragile and difficult to obtain. Another approach was to relay the beam through the articulated arm using mirrors, but the arms move and suffer routine shock and vibration, causing such designs to be unreliable. The team needed a different approach, so they decided to build a compact laser in the handpiece itself.

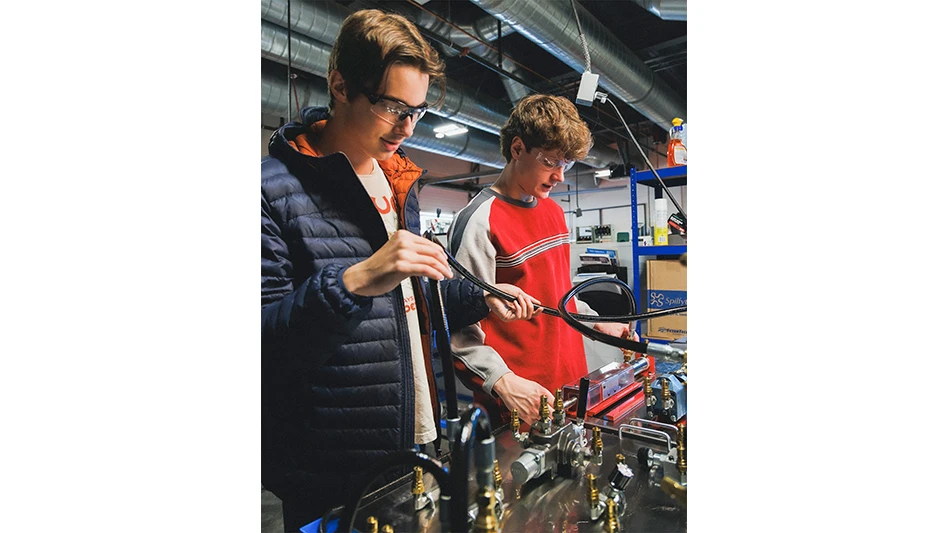

In addition to the laser rod, flashlamp, electronics, cavity mirrors, and cooling materials, the handpiece needed to include a shutter to allow beam calibration, and an XY scan assembly to direct the 6mm diameter beam over the patient's skin. There have been a few instances of lasers built into handpieces, but never with an integrated 2-axis scanner. "The MicroMo motors were one of the reasons we were able to do that," says Scott Davenport, director of product development at Cutera. In order to avoid operator hand fatigue, the unit had to be both lightweight and balanced; Cutera produced a handpiece that weighs only 1.5 lb.

Scanning Matters

The most common laser scan technology is a galvo scanner, a paddle-shaped mirror oscillated electromagnetically to shift the beam direction at up to 200Hz. Because the laser used in the Pearl handset only pulses at 20Hz, another option emerged: scanning with a stepper motor. "We didn't need the speed of the galvoor all of the problems associated with them like lack of good feedback," Davenport says. "These stepper motors are perfect because they're small and pretty trouble free. They have encoders and we can use different gearboxes to optimize what we are trying to do."

The design team produced a scanner consisting of a gimbal-mounted mirror positioned by two steppers: one to scan the beam along the X-axis and one to scan along the Y-axis. To achieve the required spatial resolution, they added a gearbox with a 64:1 reduction ratio.

Fully refining the design required the services of MicroMo's dedicated test lab. During initial shock and vibration testing, one of the stepper motors stopped working, so Cutera sent it back to MicroMo for analysis. The results revealed that the unit had been stressed between the motor and the encoder.

"We looked at our mechanical design and this motor was on the gimbal axis of the scan mirror," Davenport states. "It turned out that when the unit got dropped in testing, it swung the motor, which hit the chassis of the handpiece and actually broke. We redesigned the stops to prevent that."

The key to fixing the problem, he adds, was knowing where to look. "They analyzed it and told us what was wrong with the motor and allowed us to home in on the root cause."

The ability to adjust stepper performance by swapping out the gearbox provided a significant engineering advantage. Cutera developed a spin-off Er:YSGG product called the Pearl Fractional, which uses a diffractive beamsplitter to divide the main beam into a sextet of 300µm diameter spots, an arrangement that offers advantages for deep wrinkle removal.

The working distance and large spot array of the Pearl Fractional produced a pattern too big for the gimbal scanner of the Pearl unit. Instead, the team split the scan function between two separate mirrors, one for the X-axis and one for the Y-axis, each run by a separate stepper motor. That design accommodated the larger beam footprint; dealing with resolution came next.

The overall scan length for the fractional Pearl is less than for the standard product, but ensuring optimal coverage with the matrix of small spots requires much smaller incremental moves. To achieve this, the engineers switched to a 256:1 gearbox.

"What you are trying to balance here is speed versus resolution," Davenport says. Gearing down motor speed yields higher spatial resolution, but it also increases treatment duration, which is a concern for patient, provider, and manufacturer alike. "You basically want to optimize your speed but you also need the resolution to go with it. By choosing the appropriate gearbox, you can really dial that in and not have to compromise. For an engineer, it's a nice thing."

Here, the consistent performance of the stepper motors provided big benefits. "The fact that these motors are all the same except for the gearbox makes it really easy to change the resolution," Davenport notes. "Instead of having to alter the way you drive it or how you look at the encoder, you just switch to a different gearbox and you've changed your resolution completely."

Calibration

In medical and aesthetic lasers, safety is paramount. The beam needs to be calibrated each time it is used, and here, too, a MicroMo stepper motor comes into play. The motor controls a mirror that can be flipped into the optical path to redirect the beam into a beam dump, allowing laser calibration. That process ensures the laser is operating at the correct power levels before any light escapes.

Nearly all gearboxes exhibit some backlash, which could compromise the precision scanning required for laser treatments. Although MicroMo offers a zero-backlash product, the devices were too big for the Pearl handpiece. Instead, the team had to develop its own solution, balancing hysteresis using a preloaded return spring.

As with any medical device, the Cutera systems required approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. This can be a lengthy, even arduous process, but the combination of stepper motors and encoders simplified matters, Davenport says. "They are a really nice thing to have. When you do your hazards analysis, you have to do a device description where you tell them details of your design. I think the fact that these are stepper motors with encoders really simplifies the approval. The examiners don't ask any questions because they know that that's a good way to go."

So far, the Pearl family of products has "lit up" the aesthetic laser market. The ergonomics of the handpiece work just right, in part because the mass of the laser assembly is balanced by the stepper motors, which provide reliable, accurate performance. "We have not had any issues with them," Davenport says. "The thing that is nice about stepper motors is they are so predictable. They work great."

Explore the January February 2009 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- NextDent 300 MultiJet printer delivers a “Coming of Age for Digital Dentistry” at Evolution Dental Solutions

- Get recognized for bringing manufacturing back to North America

- Adaptive Coolant Flow improves energy efficiency

- VOLTAS opens coworking space for medical device manufacturers

- MEMS accelerometer for medical implants, wearables

- The compact, complex capabilities of photochemical etching

- Moticont introduces compact, linear voice coil motor

- Manufacturing technology orders reach record high in December 2025