Patient monitors from Philips Medical are dependable, robust, and small.Encountering Philips Medical Systems’ products occurs under either wonderful or difficult circumstances. At the Boeblingen, Germany, location, Philips develops and produces CTG devices to measure labor contractions of mothers-to-be and devices to monitor critically ill patients in intensive care unit (ICU). Complete product development process from design to production occurs at this location, with the addition of various components delivered by suppliers.

Patient monitors from Philips Medical are dependable, robust, and small.Encountering Philips Medical Systems’ products occurs under either wonderful or difficult circumstances. At the Boeblingen, Germany, location, Philips develops and produces CTG devices to measure labor contractions of mothers-to-be and devices to monitor critically ill patients in intensive care unit (ICU). Complete product development process from design to production occurs at this location, with the addition of various components delivered by suppliers.

Philips products, used in the care of patients in ICU, can monitor up to 20 parameters, including blood pressure, blood oxygen levels and EKG readings. The devices display the results, while also recording, and interpreting them. Some devices make diagnosis recommendations based on certain combined results and warn staff of possible complications such as the threat of sepsis. The monitors, per LAN or wireless, also have the ability to connect to the hospital network for central data collection.

Philips designers are responsible for creating the plastic housing and metal interior for affixing the electronic components, and for developing pneumatic systems, such as a small, integrated compressor for measuring blood pressure. Further challenges include gas induction systems, fiber optics, and systems that connect patient sensors to the monitors.

The Philips design environment is comprised of PTC’s CoCreate product family, an explicit 3D CAD software system, plus a Mentor Graphics electronics development package with a customized interface.

“Our models continue to become more and more complex because we work intensely with integral housing,” says Joerg Zwirner, head of the department. “That means that we integrate the connectors into the housing in order to simplify assembly.”

The plastic parts are highly complex. The industrial designers develop the external form – using 3D CAD software – and pass it to the mechanical designers as a sort of formed clump. They carve out the clump, determine the dimensions of the interior, and affix the highly complex fittings to the interior walls. “This works very well using explicit modeling because we are free to work on the interior walls of the housing without inadvertently altering the outer surfaces,” says Thomas Kuehnel, project manager.

One design challenge the team faces is ventilation for the devices, which has to guarantee adequate cooling while keeping out any disinfectant liquids. To accomplish this, the designers use specially formed cooling slits. And, for the development of the circuit boards, the Philips designers adhere to a rigid process that enables tight and seamless integration between electronic and mechanical development. Zwirner explains, “We are the keepers of the internal space. The electronic technicians send us roughly calculated cuboids and surfaces that symbolize the area and surface required. Together with the industrial engineer, we then define the spatial placement of the elements.”

Constantly Growing

Two areas of recent technical innovation are the diagnosis capability and the operation of the devices. Older devices, with many small knobs and buttons, and comparatively small displays, are hard to compare to today’s devices designed with touch screens that take up most all of the front surface and have the dual function of operation and readings display. In addition, new devices are regularly in development.

“We develop the components ourselves,” Zwirner says. “We have reached a very high level of design maturity, which means that our toolmakers rarely have to make any changes to the parts. This is very important because, for example, on a low rear portion of the housing, a demolding bevel made later in the process would have a significant effect on the design. We have to reckon with the unforeseen from the beginning, but our engineers are so experienced in production techniques that they can almost design directly for production.” In this way, Philips avoids any interface problems that would cause the model to go back and forth between the designers and the toolmaker.

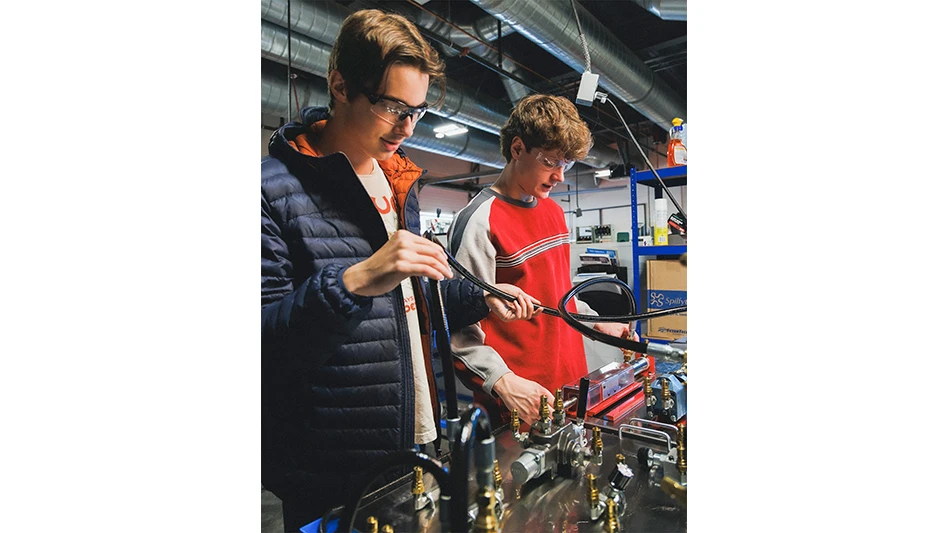

Zwirner talks about daily work in mechanical design. “We are a small group and often work with trainees and grad students and, at peak times, with other engineers on a part-time basis. Learning to use CoCreate is so simple that trainees are up and running after only two weeks. However, what is even more important for me as head of the department is that I can place my resources very flexibly on an as-need basis. Because the models do not contain constraints, any designer can work seamlessly with any colleague’s model. So it is quite easy to keep projects rolling during vacation, illness, and peak times because I can simply switch around my resources to fill in where needed.

“Explicit modeling corresponds to the way people think,” Zwirner says. “We like to put engineers from all areas together in a meeting corner with a big LCD monitor displaying the model. We can really play with the design; it is so easy to implement ideas and modification suggestions during the meeting. Ideas are not lost or forgotten and we can see immediately if they are feasible. That is a very practical way to coordinate mechanical and electronic hardware development.

“Our models are highly complex with freeform surfaces, diverse forms for integral construction, demolding bevels, casting radii and other production features. We often push the software to its limit. We think the ease-of-use factor is excellent and we love the great design freedom that CoCreate gives us. In addition, we really appreciate the flexibility the CoCreate product family from PTC gives us to place our personnel where and when best suited. We are sure that we are working with the best system for our design strategy,” Zwirner concludes.

Parametric Technology Corp.

Needham, MA

ptc.com

Philips Healthcare

Bothell, WA

healthcare.philips.com

Explore the January February 2010 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- NextDent 300 MultiJet printer delivers a “Coming of Age for Digital Dentistry” at Evolution Dental Solutions

- Get recognized for bringing manufacturing back to North America

- Adaptive Coolant Flow improves energy efficiency

- VOLTAS opens coworking space for medical device manufacturers

- MEMS accelerometer for medical implants, wearables

- The compact, complex capabilities of photochemical etching

- Moticont introduces compact, linear voice coil motor

- Manufacturing technology orders reach record high in December 2025