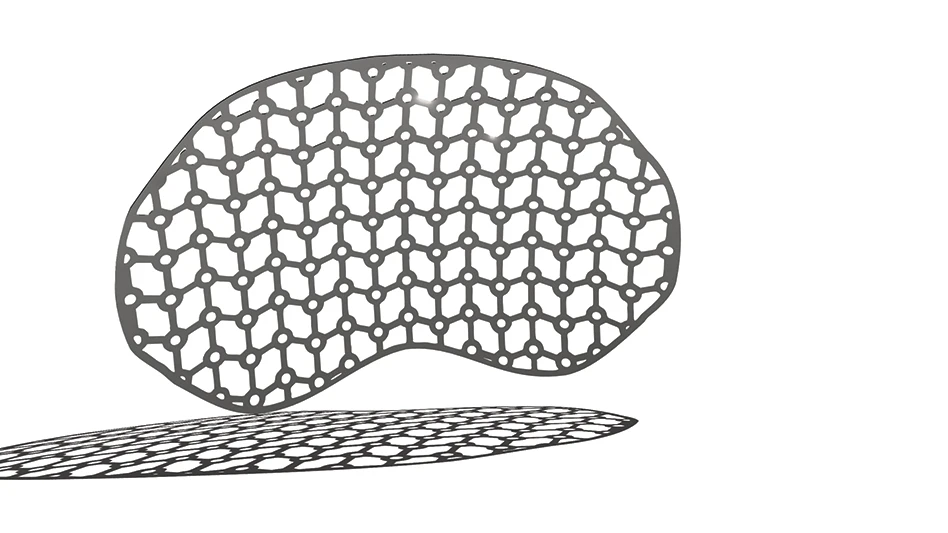

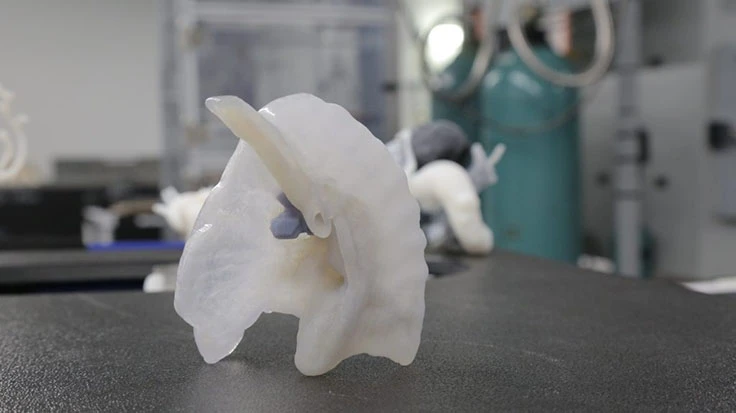

A scaled-down version of 3D-printed lungs. Image credit: GE Healthcare/GE Reports.

3D printing continues to grow by leaps and bounds - and there are few companies that aren't looking at ways to advance this manufacturing technology faster than it's already grown. A recent post on GE Reports shows how one engineer is pushing to translate CT sans to printed models. 3D customized implants are already changing and saving lives. 3D's use is expanding in plants. 3D printed prosthesis are changing people's lives for the better...and it's not going to slow anytime soon.

Jimmie Beacham, chief engineer for advanced manufacturing at GE Healthcare, and his team at the company’s futuristic laboratory in Waukesha, Wisconsin, are looking for ways to quickly and efficiently translate image files from computed tomography (CT) scanners and other imaging machines so they can be printed.

“Today, when people print organs, it can take anywhere from a week to three weeks to manipulate the data,” Beacham says. “We want to do it with a click of a button.”

It’s not an easy task. A CT scanner like GE’s Revolution CT generates and transmits in 1 second an amount of data equivalent to 6,000 Netflix movies.

“Right now, we convert all that data into an image on the screen,” Beacham says. “I’m pushing our teams across GE Healthcare to look at how we can create a software package that turns that image into a printable file that can be sent to a 3D printer. We’ve already printed several organs like the liver and the lung. It’s valuable learning.”

GE Additive is a business unit that’s developing machines for 3D-printing and other additive manufacturing methods. As a next step, Beacham’s team is collaborating with GE Additive to explore whether “a custom machine that prints organs from the files that we derive from our software” makes sense. Given the industry’s advancements, Beacham says, speed is of the essence. “If we don’t figure it out, someone else will,” he says.

Beacham says that anatomical replicas of organs would provide the surgeon with more information upfront. “Surgeons sometimes have to repeatedly go to a workstation, look at the image on the screen and try to figure out what’s going on,” he says. “It slows the surgery down and increases the odds of introducing infection or slowing the patient’s recovery time.”

3D-printed anatomical replicas will also help clarify things, Beacham says. “I think as people get more informed about health, they will want to be a bigger part of the solution. Helping them see the problem clearly will build more trust between the doctor and the patient.”

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- Stryker’s flexible syndesmotic fixation device stabilizes ankle injuries

- Mergers & acquisitions news: MGS, Quantum Surgical bolster medtech portfolios

- Exchangeable-head solid carbide cutting tools

- NextDent 300 MultiJet printer delivers a “Coming of Age for Digital Dentistry” at Evolution Dental Solutions

- Get recognized for bringing manufacturing back to North America

- Adaptive Coolant Flow improves energy efficiency

- VOLTAS opens coworking space for medical device manufacturers

- MEMS accelerometer for medical implants, wearables