Kaiba is the first child to receive novel 3D-printed tracheal splints, which helped keep his airways open, restored his breathing, and saved his life. He is now an active preschooler. The boy’s own tissues have successfully taken over the job of the implant, which has been almost completely reabsorbed by his body (Credit: Leisa Thompson, Photography/UMHS).

Ann Arbor, Michigan – An adolescent girl has now joined a group of three baby boys and one baby girl who have received novel 3D-printed tracheal splints to treat a congenital breathing condition called tracheobronchomalasia (TBM). It is estimated that one in every 2,000 children is affected by this life-threatening condition worldwide. All five patients continue to thrive thanks to the surgical procedures that have helped their collapsed airways function normally. The lifesaving procedures took place under FDA Emergency Clearance. EOS provided expert advice and additive manufacturing technology.

Challenge

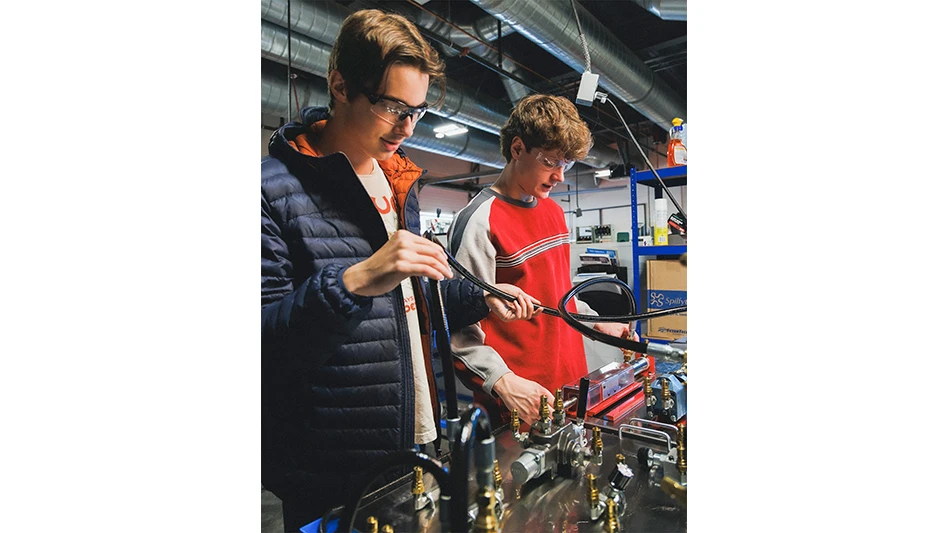

Dr. Glenn Green, a pediatric otolaryngologist, and his surgical team from C.S. Mott Children's Hospital, Ann Arbor, joined forces with Dr. Scott Hollister, professor of biomedical engineering at the University of Michigan, to pioneer the patient-specific medical device designs. “It's now pretty automatic to generate an individualized splint design and print it; the whole process only takes about two days now instead of three to five," explains Dr. Hollister. However, there were some challenges to overcome in achieving this success.

How did the relatively small university team achieve this feat of creating surgery-ready implants on an academic research budget? Computer-aided design (CAD) sped up the engineering side and 3D printing provided cost-effective, patient-specific production. “Even if a market is relatively small, this doesn't diminish the human need to be treated," says Dr. Hollister, who first learned about Additive Manufacturing in the 1990s. “Later, when I started designing my own porous scaffolds for anatomic reconstruction, I realized that 3D printing would be useful for creating the complex geometries I had in mind."

For a number of reasons, polycaprolactone (PCL) was found to be the perfect material for additively manufacturing a tracheal implant: First, it has a long resorption time, which is very important in airway applications, because the implant needs to remain in place for at least two years before it is resorbed. Second, PCL is very ductile, so if it fails, it will not produce any particles that might puncture tissue. Third, PCL can be readily processed for, and fabricated on, the EOS system.

.jpg) Solution

Solution

Dr. Hollister and the University of Michigan had already purchased a Formiga P 100 in 2006 to aid research into scaffolds and biomaterials. “I chose EOS because we were looking for a system that was flexible and allowed us to change parameter settings like laser power, speed, powder-bed temperature, and so on, which we needed to do to customize our builds," says Dr. Hollister. “Also, because biomaterials can be expensive and implants and scaffolds are typically not so big, we wanted a more limited build volume that didn't use a lot of material. The Formiga P 100 fitted the bill for both of these requirements."

“If we can expand the number of biomaterials used in Additive Manufacturing, we can tackle a tremendous number of problems in all fields of reconstructive surgery and make enormous strides for the benefit of patients." ~ Dr. Scott Hollister, Professor of Biomedical Engineering and Lead Researcher at the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University of Michigan

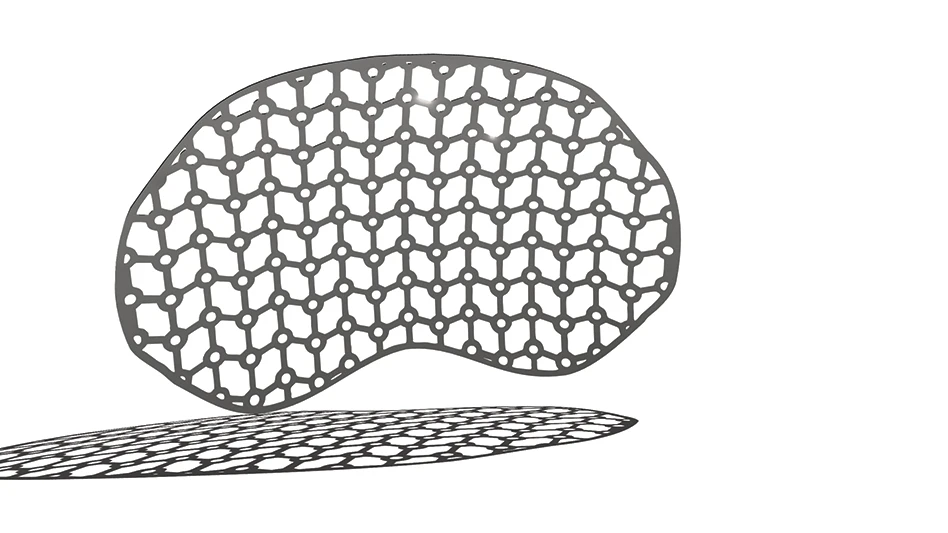

ABOVE: Two of the University of Michigan's groundbreaking 3D printed tracheal splints, made of polycaprolactone (PCL) using EOS technology, on a model of a trachea (Credit: Leisa Thompson, Photography/UMHS).

The University team uses patient data from MRI or CT scans to examine the defect to be repaired, then creates computer models of the anatomy. Engineers are then able to design splints with a highly compliant, porous structure of interconnected spaces, which will slowly expand along with the maturing airway over time. “EOS even gave us access to software patches, to enable us to change the range of parameters of the machine to best process the PCL material," says Dr. Hollister.

Results

Finally, the splint was produced using the FORMIGA P 100 system. “Additive manufacturing is one of the few methods I know that allows us to actually fabricate these complex designs," says Dr. Hollister. After fabrication, the researchers measure the splint dimensions and then mechanically test them. The splint-supported trachea expands and is operational right away, so that when patients are weaned off oxygen, they are able to breathe normally. The first child is now nearly four years old and an active preschooler. And, as planned, the boy's own tissues have successfully taken over the job of the implant, which has been almost completely reabsorbed into his body.

Dr. Hollister's group is also developing craniofacial, spine, long bone, ear and nose scaffolds and implants – and producing them all using additive manufacturing technology from EOS, using a material with characteristics that promote reconstruction and regrowth following birth defects, illnesses or accidents. While 3D printing is being adapted to serve an ever-widening breadth of industrial applications, it is this kind of clinical translation of the technology to individual patient-specific solutions that is making life-altering history in the field of medicine.

Dr. Green says that his office is continually receiving phone calls and emails from parents and doctors enquiring about these implants. The future role of additive manufacturing in the medical field is clearly wide open, Dr. Hollister believes. “I see a time soon, probably within the next five years, when many hospitals and medical centers will print their own devices specifically for their own patients, and not need to get them off-the-shelf."

The University of Michigan is one of the world’s most distinguished universities. Founded in 1817 in Detroit, it relocated to Ann Arbor in 1841. Its biomedical engineering department supports one of the largest healthcare complexes in the world.

Source: EOS

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- Stryker’s flexible syndesmotic fixation device stabilizes ankle injuries

- Mergers & acquisitions news: MGS, Quantum Surgical bolster medtech portfolios

- Exchangeable-head solid carbide cutting tools

- NextDent 300 MultiJet printer delivers a “Coming of Age for Digital Dentistry” at Evolution Dental Solutions

- Get recognized for bringing manufacturing back to North America

- Adaptive Coolant Flow improves energy efficiency

- VOLTAS opens coworking space for medical device manufacturers

- MEMS accelerometer for medical implants, wearables