University of Glasgow engineers, who have previously developed an electronic skin covering for prosthetic hands made from graphene, have found a way to use some of graphene’s remarkable physical properties to use energy from the sun to power the skin.

Graphene is a highly flexible form of graphite which, despite being just a single atom thick, is stronger than steel, electrically conductive, and transparent. It is graphene’s optical transparency that allows close to 98% of the light that strikes its surface to pass directly through it, ideal for gathering energy from the sun to generate power.

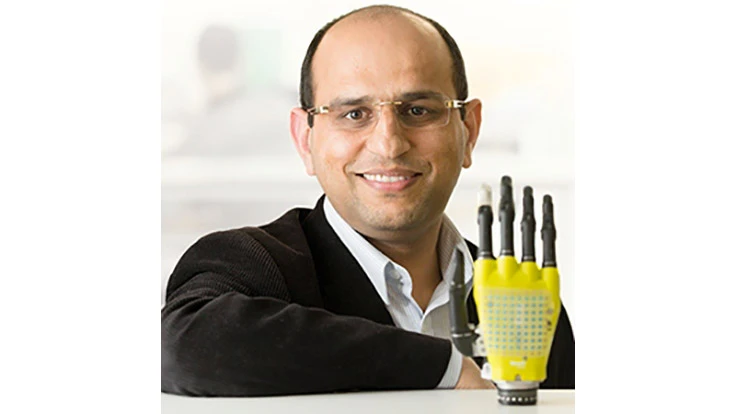

A new research paper in the Advanced Functional Materials describes how Dr. Dahiya and colleagues from his Bendable Electronics and Sensing Technologies (BEST) group have integrated power-generating photovoltaic cells into their electronic skin for the first time.

Dahiya, from the University of Glasgow’s School of Engineering, says: “Human skin is an incredibly complex system capable of detecting pressure, temperature and texture through an array of neural sensors which carry signals from the skin to the brain.

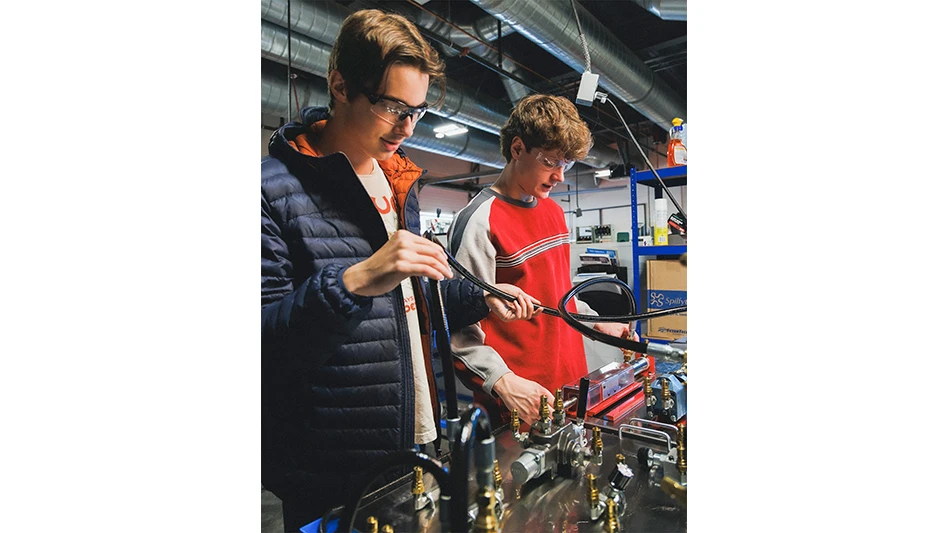

“My colleagues and I have already made significant steps in creating prosthetic prototypes which integrate synthetic skin and are capable of making very sensitive pressure measurements. Those measurements mean the prosthetic hand is capable of performing challenging tasks like properly gripping soft materials, which other prosthetics can struggle with. We are also using innovative 3D printing strategies to build more affordable sensitive prosthetic limbs, including the formation of a very active student club, Helping Hands.

“Skin capable of touch sensitivity also opens the possibility of creating robots capable of making better decisions about human safety. A robot working on a construction line, for example, is much less likely to accidentally injure a human if it can feel that a person has unexpectedly entered their area of movement and stop before an injury can occur.”

The new skin requires 20 nanowatts of power per square centimeter, and, although currently energy generated by the skin’s photovoltaic cells cannot be stored, the team are already looking into ways to divert unused energy into batteries to be used as and when required.

“The other next step for us is to further develop the power-generation technology which underpins this research and use it to power the motors which drive the prosthetic hand itself. This could allow the creation of an entirely energy-autonomous prosthetic limb,” Dahiya adds. “We’ve already made some encouraging progress in this direction and we’re looking forward to presenting those results soon. We are also exploring the possibility of building on these exciting results to develop wearable systems for affordable healthcare. In this direction, recently we also got small funds from Scottish Funding Council.”

The team’s paper, Energy Autonomous Flexible and Transparent Tactile Skin, is published in Advanced Functional Materials. The research was funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC).

Latest from Today's Medical Developments

- NextDent 300 MultiJet printer delivers a “Coming of Age for Digital Dentistry” at Evolution Dental Solutions

- Get recognized for bringing manufacturing back to North America

- Adaptive Coolant Flow improves energy efficiency

- VOLTAS opens coworking space for medical device manufacturers

- MEMS accelerometer for medical implants, wearables

- The compact, complex capabilities of photochemical etching

- Moticont introduces compact, linear voice coil motor

- Manufacturing technology orders reach record high in December 2025